Oregon’s Land Use Legacy at Risk: Oppose SB 1522-1

This testimony was submitted publicly to the Oregon State Legislature on February 12th, 2026 here.

Testimony Opposing Senate Bill 1522 (-1 Amendment): A Defense of Economic Certainty, Agricultural Heritage, and the Oregon Land Use Legacy

Executive Summary: The Stewardship of Certainty

This testimony is submitted to the Senate Committee on Housing and Development in fierce and unequivocal opposition to Senate Bill 1522, specifically the -1 amendment. We write this not merely as observers of the legislative process, but as lifelong Oregonians, as active participants in the state’s economic development through the Pegasus Equestrian destination resort, and with direct experience with the foundational leadership that established the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) over fifty years ago. This testimony has been written by the Millegan Brothers, Drew Millegan & Quinn Millegan, on behalf of Millegan Brothers, Millegan Media, & Pegasus Equestrian International. As young professionals (30 & 27), we represent Oregon’s next generation.

The proposed amendment to SB 1522 represents a catastrophic departure from the core tenets of Oregon’s land use planning system—a system that has successfully balanced urban growth with the preservation of the natural resources that form the backbone of our state's economy. By prohibiting considerations for avoiding resource lands when designating urban reserves, this bill does not merely adjust a procedural dial; it effectively mandates that cities look to our most valuable farm and forest lands first, rather than last, for expansion. It creates a legislative mechanism that incentivizes the consumption of the Willamette Valley’s prime agricultural soils—the "factory floor" of our second-largest industry—in favor of sprawling, low-density development that serves neither the housing crisis nor the long-term fiscal health of our municipalities.

Our opposition is grounded in a unique intersection of perspectives. We are hedge fund managers & developers who are planning to bring hundreds of millions of dollars into a rural destination resort, having navigated the rigorous approval process of the current system. We are agricultural stakeholders who understand that the "certainty" provided by Urban Growth Boundaries (UGBs) is the only reason farmers plant orchards with forty-year maturation cycles. Our family also has experience working at LCDC when these rules were developed and why they were so broadly supported by Oregonians.

It is a rare day when a large-scale developer stands shoulder-to-shoulder with 1000 Friends of Oregon. We have litigated against each other; we have sat on opposite sides of the courtroom in the Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA). Yet today, we stand united. This unity underscores the gravity of the threat SB 1522 poses. We recognize, as they do, that the Oregon system is not a barrier to prosperity, but the very foundation of it. This report will demonstrate, through historical analysis, economic data, and fiscal impact studies, that SB 1522 is a regressive policy that threatens to dismantle the economic certainty required for Oregon’s future.

Part I: The Historical Imperative – A Legacy at Risk

To understand why SB 1522 is so dangerous, one must first understand the crisis that necessitated Oregon’s land use laws and the monumental effort required to establish them. The protections this bill seeks to strip away were not placed there by accident; they were the result of a hard-fought battle to save the state from economic and environmental ruin.

1.1 The Crisis of the 1960s and the "Sagebrush Saboteur"

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Oregon stood at a precipice. The post-war economic boom had brought with it a wave of rapid, unchecked suburbanization. The Willamette Valley, home to some of the most fertile Class I and II soils in the world, was being devoured by subdivision after subdivision. This was not merely an aesthetic loss; it was an economic hemorrhage. The valley constitutes only a small percentage of the state's landmass but generates the vast majority of its agricultural wealth.

Governor Tom McCall | Oregon Secretary of State, distributed by Marion County, Oregon to voters without a copyright notice.

Governor Tom McCall, a Republican journalist-turned-statesman, saw this trajectory and recognized it as an existential threat to the Oregon way of life. In his legendary opening address to the 1973 Legislative Assembly, McCall railed against the "sagebrush saboteur" and the "ravenous rampage of suburbia". [1] He warned that without state intervention, Oregon would become a seamless concrete corridor from the Columbia River to the California border, stripped of the natural resources that defined its economy. McCall’s rhetoric was not hyperbole; it was a description of the reality unfolding in states like California and New Jersey, where prime farmland was being irreversibly converted into strip malls and tract housing.

1.2 The Charbonneau Catalyst: "Jumping the River"

While McCall’s speeches provided the moral momentum, the political will for Senate Bill 100 (the statutory foundation of our land use system) was crystallized by a specific, controversial event: the development of Charbonneau.

Located in Wilsonville, Charbonneau was a planned community that famously "jumped the river," crossing the Willamette to build on prime agricultural land south of the river. [3] This development was a visceral example of leapfrog sprawl—development that bypasses existing urban infrastructure to consume cheaper rural land, leaving the public to pick up the tab for extending services. The "Charbonneau controversy" became the smoking gun for land use advocates. [1] It demonstrated that local control, left unchecked, would inevitably succumb to the short-term pressure of development capital, sacrificing the long-term public interest in resource land.

Charbonneau proved that without a statewide framework, cities would always choose the path of least resistance. It is far easier for a developer to bulldoze a flat farm field than to redevelop a brownfield or infill an existing neighborhood. SB 1522, by removing the requirement to avoid resource lands, effectively invites a thousand new Charbonneaus. It erases the primary lesson learned half a century ago: that if you do not legally protect farm land, the market will inevitably consume it.

1.3 Senate Bill 100 and the "Original Seven"

Passed in 1973, Senate Bill 100 created the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC). The first commission was not a group of faceless bureaucrats but a collection of civic titans who understood the weight of their task. Appointed by Governor McCall, these "Original Seven" were charged with drafting the Statewide Planning Goals that would govern Oregon land use for generations. [2]

Among them was L.B. Day, a Teamster official and fierce political operator who served as the first Chairman. [7] Day’s leadership was characterized by a pragmatic, forceful approach to consensus. He famously rejected initial drafts of the goals for being too weak, demanding a framework that had teeth. Alongside him were figures like Dorothy Anderson, a League of Women Voters stalwart who brought rigorous intellectual scrutiny to the process, ensuring that the goals were legally sound and publicly defensible. [7]

Our father’s involvement during these early years provided our family with a front-row seat to the creation of this system. We learned that the "Goals"—specifically Goal 3 (Agricultural Lands), Goal 4 (Forest Lands), and Goal 14 (Urbanization)—were designed as a tripod. They function as an interlocking system. Goal 3 protects the soil; Goal 14 forces cities to grow efficiently. Remove the priority of protecting resource land under Goal 14 (which SB 1522 does), and the entire structure collapses. The system relies on the tension between these goals to produce rational outcomes. SB 1522 removes the tension and replaces it with a trapdoor.

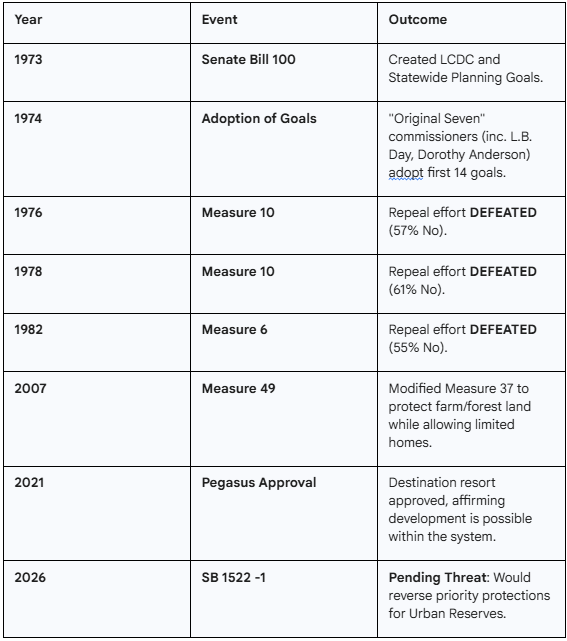

1.4 The Voter Mandate: A Triple Affirmation

Opponents of Oregon’s land use planning have long argued that the system is a top-down imposition by the state on the will of the people. History refutes this narrative definitively. The land use system was subjected to repeal referendums on the statewide ballot three times: in 1976, 1978, and 1982. [4]

In each instance, Oregonians voted to keep the system. Crucially, the margins of victory increased over time. In 1976, the system survived by a modest margin. By 1982, after voters had seen the results—distinct cities, preserved farmland, and accessible nature—the support was overwhelming. The people of Oregon effectively ratified SB 100 three times over. This is not just a policy; it is a social contract. SB 1522 attempts to undo via legislative amendment what the voters have repeatedly affirmed at the ballot box: that farm and forest lands are to be protected, not paved.

Part II: The Architecture of Stability – Understanding the Threat

To appreciate the damage SB 1522 -1 will cause, one must understand the mechanics of the current Urban Reserve system and how the amendment dismantles it. The current law is built on a hierarchy of land values; the amendment proposes a flat landscape where a hazelnut orchard is treated with the same disregard as a scrub lot.

2.1 The Urban Growth Boundary (UGB) and Goal 14

Goal 14 establishes the Urban Growth Boundary (UGB) to distinguish urbanizable land from rural land. It is a mechanism of efficiency. It forces cities to use land inside the boundary efficiently before expanding outward. However, cities need to plan for the long term—typically 20 to 50 years out. This is where Urban Reserves come in.

Urban Reserves are the designated "waiting rooms" for future UGB expansion. They are the lands a city identifies today as the places it will grow tomorrow. Under current statute (ORS 195.145), the designation of these reserves is governed by a strict priority system. When drawing the lines for Urban Reserves, cities and counties must look to lands in the following order:

Exception Lands: Lands already committed to residential or non-resource use (e.g., rural residential zones).

Marginal Lands: Lands with poorer soils or topographical challenges that make them unsuitable for commercial agriculture.

Resource Lands: High-value farm (EFU) and forest lands. These are to be looked to last, and only if the need cannot be met by the first two categories. [12]

This hierarchy is the only thing standing between the bulldozer and the blueberry field. It forces jurisdictions to do the hard work of infill, redevelopment, and utilizing lower-quality land before they are permitted to consume the state's prime economic assets.

2.2 The -1 Amendment: A License to Sprawl

SB 1522 -1 removes this hierarchy. The amendment explicitly prohibits any considerations for avoiding resource lands. It strips the requirement to treat EFU and Forest land as a last resort.

In practice, this means a city planner or city council, faced with the choice between expanding into a complex, parcelized rural residential area (which requires dealing with hundreds of individual homeowners) or expanding into a 500-acre contiguous hazelnut orchard (owned by a single entity), will be legally permitted—and economically incentivized—to choose the orchard. The orchard is flat, cleared, and easy to grade. It is the path of least resistance.

By removing the legal friction that protects resource lands, SB 1522 creates a perverse incentive: the best land for farming is often the easiest land to develop structurally. Without the statutory mandate to avoid it, the market will consume it. This is not "flexibility"; it is capitulation to sprawl.

2.3 The "Placeholder" Deception

It is also worth noting the procedural manner in which this change has been introduced. HB 1522 was originally filed as a "placeholder" bill—a legislative vessel with no substantive content, kept alive for late-session maneuvers. The -1 amendment, which completely upends decades of land use law, was submitted late in the process, minimizing the opportunity for public scrutiny and debate.

This "gut and stuff" tactic is a disservice to the magnitude of the policy change. A revision of Goal 14 priorities should be the subject of interim committees, broad stakeholder engagement, and transparent analysis—not a last-minute amendment to a zombie bill. This procedural slight of hand suggests that the proponents know the policy cannot withstand the light of day.

Part III: The Economic Argument – Certainty as Currency

The proponents of SB 1522 likely frame their argument in terms of housing supply and land availability. However, from a business perspective, they are ignoring the single most valuable commodity the Oregon land use system provides: Certainty. For economic development to occur—whether it is planting a hazelnut orchard, building a high-tech fabrication plant, or developing a destination resort like Pegasus Equestrian—investors need to know what the rules are and that they will remain in place.

3.1 The Value of Regulatory Stability

Capital is cowardly; it flees uncertainty. In many states, land use is a chaotic free-for-all where zoning changes depend on which developer has the mayor's ear this week. In Oregon, the UGB and the rigid criteria for expansion provide a stable playing field.

Farmers know that their investment in irrigation and soil amendment is safe because the UGB won't arbitrarily jump the fence. Developers know where growth will occur and can invest in infrastructure accordingly. This stability reduces risk premiums and encourages long-term capital deployment. SB 1522 introduces volatility into this system. If any piece of farmland can be designated as an Urban Reserve without a rigorous priority analysis, no rural landowner can predict the future of their property.

3.2 Case Study: Pegasus Equestrian

Our perspective is informed by the development of Pegasus Equestrian, a major destination resort in Douglas County encompassing over 2,800 acres. [13] This project was approved under Oregon's strict land use laws, but it was not easy.

It is no secret that we have battled 1000 Friends of Oregon in the past. They challenged our approval multiple times, leading to hearings before the Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA) and the Oregon Court of Appeals. [14] We spent years and significant financial resources defending our project. In every instance, Pegasus prevailed. We won because we followed the rules. We won because the system provides a framework where if you meet the rigorous criteria, you can proceed.

Why is this relevant to SB 1522? Because our experience demonstrates that the current system works. It is rigorous. It allows for opposition and review. But ultimately, it provides a pathway for legitimate economic development that complies with the law.

More importantly, the value of our resort relies on the rural character of the surrounding landscape. We will invest hundreds of millions of dollars [15] based on the "certainty" that the land use system would prevent the rolling hills of Douglas County from becoming a sprawl of strip malls and tract housing. If SB 1522 passes, that certainty evaporates. If the farm next door can be redesignated as an urban reserve overnight, the rural aesthetic that underpins the value of our resort is diminished. We fought 1000 Friends to build our project, but we join them today to save the system that gives our project value and provides hundreds of jobs.

3.3 The Irony of Alignment

The fact that Pegasus Equestrian and 1000 Friends of Oregon are aligned on this issue should signal to the committee that SB 1522 is an outlier. It is not a "pro-business" bill versus an "environmental" bill. It is a "bad policy" bill. When the developers who navigate the system and the watchdogs who police it both agree that a change is destructive, the legislature should listen. After challenging our approvals, 1000 Friends lost and paid our legal fees in the past [14]; today, we offer them our support. This alliance serves as a testament to the fact that the Oregon system, for all its friction, is the bedrock of our mutual interests.

Part IV: The Agricultural Superpower – Protecting the Factory Floor

Proponents of SB 1522 creates a false dichotomy between housing and agriculture, implying that we have plenty of "empty" land to spare. This ignores the sheer economic scale of Oregon agriculture. We are not protecting scenery; we are protecting the factory floor of Oregon’s second-largest industry.

4.1 The Willamette Valley: A Global Anomaly

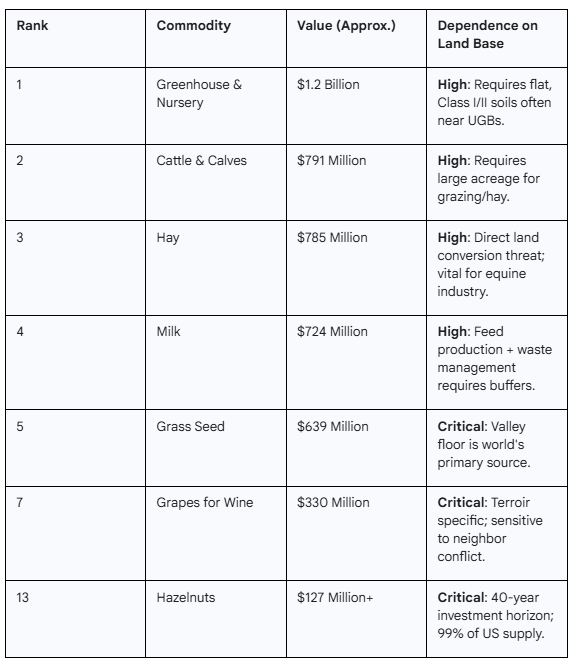

The Willamette Valley is one of the few places on Earth where climate, rainfall, and soil classification converge to create an agricultural powerhouse. It is the primary reason Oregon exists as an economic entity. The top commodities for 2024-2025 paint a clear picture of what is at stake, and how dependent these industries are on the land base SB 1522 threatens.

Table 1: Oregon’s Top Agricultural Commodities & Land Dependency

Preserving these industries requires land base certainty.

Source Data: [17]

4.2 The Hazelnut Industry: A Case Study in Long-Term Investment

Oregon produces 99% of the hazelnuts in the United States. [22] This is not a casual crop; it is a permanent crop. A hazelnut orchard requires a massive upfront investment in trees, irrigation, and establishment, and it takes years to reach peak production.

The industry is currently in a boom phase, with acreage tripling in the last 15 years to nearly 100,000 acres. [23] Major global players like Ferrero (makers of Nutella) and local processors like George Packing Company are investing heavily in infrastructure. [22] The "June Profit Share" distributed to growers [24] is a direct result of this global dominance.

This investment is predicated on the absence of Impermanence Syndrome. Impermanence Syndrome occurs when farmers believe that urbanization is inevitable. [25] When a farmer sees a UGB expanding or an urban reserve designation on their neighbor's land, they stop planting trees. They stop repairing barns. They stop buying new equipment. They wait to sell to the developer.

SB 1522 injects a lethal dose of Impermanence Syndrome into the valley. If cities can grab hazelnut orchards for urban reserves without having to justify why they aren't using non-resource land, no farmer can confidently plant a tree that will produce for 40 years. The "certainty" of the land use system is the only thing that makes a 40-year agricultural investment rational in a peri-urban county.

4.3 The Wine Industry: Premium Brand Equity

Oregon’s wine industry faces a similar threat. The value of Oregon wine is tied to its "origin"—the specific terroir of the Willamette Valley. The industry generates over $7 billion in total economic activity [27] and supports tens of thousands of jobs.

Vineyards are highly sensitive to land use conflicts. Drifting sprays from suburban gardens, complaints about tractor noise, and the visual degradation of the landscape all threaten the viability of the wine industry. But more importantly, the brand of Oregon wine is built on the image of stewardship and rural beauty. Replacing vineyards with sprawling subdivisions dilutes that brand equity.

The median price per ton for Pinot Noir grapes 28 and the global reputation of the region are economic dividends paid by SB 100. SB 1522 proposes to liquidate these dividends for a short-term housing fix that is likely illusory.

Part V: The Equine Industry and Rural Character

As owners of Pegasus Equestrian, we must speak for a sector often overlooked in standard agricultural reports: the Equine Industry. While horses are sometimes viewed as a hobby, they are in fact a massive economic driver in Oregon, intersecting agriculture, tourism, and sport.

5.1 Economic Impact and "Top Five" Status

The equine industry is a significant contributor to the state's economy. The American Horse Council’s economic impact studies consistently show that the horse industry contributes billions to the national economy and supports millions of jobs. [29] In Oregon, the equine sector supports a vast ecosystem of direct and indirect economic activity.

Direct Agriculture: The health of the equine industry is directly tied to the Hay market, Oregon’s #3 crop ($785 million). [17] Horses are primary consumers of local forage.

Rural Employment: The industry supports high-skill rural jobs, including veterinarians, farriers, trainers, and facility managers.

Tourism: Events at facilities like Pegasus plan to draw competitors from across the nation and internationally. [31] These visitors fill hotels, eat in local restaurants, and buy fuel, effectively importing wealth into rural counties. This is a project that garnered the written support of:

Statewide Organizations: Sport Oregon, Travel Oregon

Municipalities: Douglas County, City of Elkton, City of Drain, City of Cottage Grove, City of Sutherlin

Local Travel Organizations: Travel Lane County, Travel Southern Oregon,

Equestrian Organizations: United States Equestrian Federation, United States Eventing Association, Oregon Hunter Jumper Association, Oregon Horse Council, KB Sport Horses, Oregon Dressage Society, Morgan Horse Association, International Mountain Trail Challenge Association, Northwest Miniature Horse Club, Jumps & Jodhpurs Pony Club, Flying Change Farms, Southern Oregon Horse and Carriage Club, Duchess Sanctuary, Farwood USDA CEM Quarantine Center

5.2 The Threat of the "Urban Fringe"

Equine facilities require large tracts of land—often 20 to 100 acres or more. Because of the need for accessibility, they are often located on the "urban fringe," the exact zone SB 1522 targets for Urban Reserves.

If SB 1522 passes, the land values on the fringe will skyrocket, driven by speculation. A horse farm owner will face immense pressure to sell to developers. Furthermore, the operational reality of running a large facility—managing manure, handling large animals, hosting noisy events—becomes impossible if the property is surrounded by dense subdivisions. The "Right to Farm" laws can only do so much when the political pressure of thousands of new suburban voters bears down on a rural operation.

The Oregon Horse Council has fought for years to ensure fairgrounds and event centers receive funding and protection. [31] SB 1522 undermines this by prioritizing suburbanization over the "rural infrastructure" that supports the equine lifestyle. We need "certainty" that our investments in arenas, barns, and trails will not be zoned out of existence. The Pegasus facility is proof that world-class equestrian venues can coexist with Oregon's land use laws—but only if those laws protect the rural context required for them to exist. If Oregon’s land use laws were to be gutted, we could not invest in Oregon.

Part VI: The Fiscal Irresponsibility of Sprawl

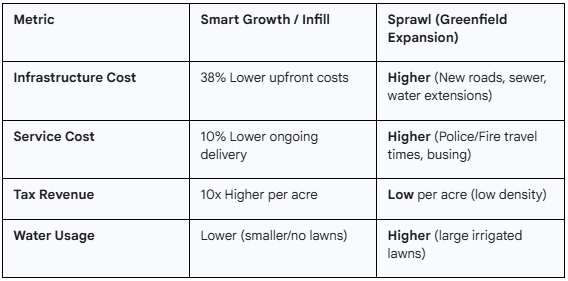

The proponents of SB 1522 likely argue that expanding onto farm land will lower housing costs. This is "land supply economics" from the 1950s, and it has been debunked by decades of fiscal impact analysis. Expanding UGBs into resource land is not a solution to affordability; it is a recipe for municipal bankruptcy.

6.1 The Cost of Services: Sprawl is a Subsidy

Development on the urban fringe is the most expensive form of growth for the taxpayer. When a city expands into an Urban Reserve on farm land (Greenfield development), it must build everything from scratch: new roads, new sewer lines, new water mains, new fire stations, and new schools.

Studies by the League of Oregon Cities and Smart Growth America consistently show that the tax revenue generated by low-density sprawl does not cover the long-term maintenance liabilities of the infrastructure required to serve it. [32]

Table 2: Economic Impact of Smart Growth vs. Sprawl

Why "Urban Reserves" on farm land cost taxpayers more.

Source Data derived from Smart Growth America & League of Oregon Cities Studies [32]

By removing the barrier to designating farm land as urban reserves, SB 1522 encourages cities to take the path of fiscal irresponsibility. It allows them to bypass the harder work of upzoning and infrastructure maintenance in favor of expanding their liability footprint. It privatizes the profits of development (for the builders of subdivisions) while socializing the costs of infrastructure onto existing ratepayers.

6.2 The "Missing Middle" Solution

The housing crisis in Oregon is real. But it is not caused by a lack of raw land; it is caused by a lack of housing diversity and a history of exclusionary zoning.

"Middle Housing"—duplexes, triplexes, cottage clusters, and townhomes—is the solution that respects the UGB. [35] Oregon has led the nation in legalizing these forms of housing (HB 2001). We are just beginning to see the fruits of this policy.

SB 1522 undermines the Middle Housing revolution. If developers can easily access "greenfield" sites on former farm land, they will default to building large, single-family detached homes—the most profitable and least efficient housing type. This does nothing to solve the affordability crisis for the workforce; it simply creates more high-end suburbs. We should be doubling down on density within the UGB, where services already exist, not opening the floodgates to sprawl outside it.

6.3 The Loss of "Exception Lands" Utilization

The current system requires cities to look at "Exception Lands" (rural residential areas) before Resource Lands. Proponents of SB 1522 hate this because Exception Lands are harder to develop. They are already parcelized; they have existing homes; they require assembly.

But from a planning perspective, this is exactly where growth should go. These lands are already impacted. They are already "quasi-urban." Converting them to full urban density makes sense. Converting a producing hazelnut orchard to urban density is a waste of a productive asset. SB 1522 allows cities to skip the Exception Lands entirely, leaving them as inefficient rural sprawl while consuming the productive farmland next door. This is bad planning, plain and simple.

Part VII: Conclusion – A Call to Honor the Contract

Fifty years ago, Governor Tom McCall stood before the legislature and asked whether Oregon would be "a poor-man's California." He asked us to choose between the "quick buck" of speculation and the enduring wealth of our land.

We chose the land. We chose it in 1973 with Senate Bill 100. We reaffirmed it in 1976, 1978, and 1982 at the ballot box. We have built an economy worth billions on the foundation of that choice—an economy of hazelnuts, wine, grass seed, and world-class equestrian sport.

Senate Bill 1522, with its -1 amendment, asks us to unmake that choice. It asks us to forget the lessons of Charbonneau. It asks us to betray the vision of L.B. Day, Dorothy Anderson, and the Original Seven. It asks us to sacrifice the "certainty" of our second-largest industry for the temporary convenience of easy sprawl.

As lifelong Oregonians, as sons of the LCDC generation, and as business owners who have navigated and succeeded within this system, we urge you to reject this bill. We have fought hard to build Pegasus Equestrian within the rules. Do not change the rules now to favor those who are unwilling to do the same. Do not dismantle the legacy that makes Oregon, Oregon.

We fiercely OPPOSE SB 1522 -1.

Appendix: Reference Timeline

Table 3: Timeline of Oregon Land Use Affirmation

Voter and Legislative History demonstrating the mandate for protection.

Source Data: [7]

Works cited

no place for nature - the limits of oregon's land use program in protecting fish and wildlife habitat in the willamette valley, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/no_place_for_nature.pdf

25th Anniversary of Oregon, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.oregon.gov/LCD/OP/Documents/25thanniv.pdf

Comprehensive Plan - Let's Talk, Wilsonville!, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.letstalkwilsonville.com/4405/widgets/13781/documents/6526

An Oral History of the Visions and Intentions Behind Oreaon's Land Conservation and Development Act: Senate Bill 100 - CORE, accessed February 12, 2026, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/36684657.pdf

THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD: FARMLAND PROTECTION IN OREGON 1961 – 2009, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.jeffco.net/media/24056

African American Resources in Portland, Oregon, from 1851 to 1973, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/mpd_final.pdf

A Brief Portrait of Multimodal Transportation Planning in Oregon and the Path to Achieving It, 1890-1974, accessed February 12, 2026, https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/40456/dot_40456_DS1.pdf?

LAND USE PLANNING INFORMATION FOR THE CITIZENS OF OREGON, accessed February 12, 2026, https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/downloads/fj2366373

Interview with Dorothy Anderson, accessed February 12, 2026, https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1062&context=planoregon_interviews

History of Land Use Planning, accessed February 12, 2026, https://multco.us/file/b.7_history_of_land_use_planning_%28state_of_oregon%29_4.7.2020/download

Land Use Planning - The Oregon Encyclopedia, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/land_use_planning/

SB1522 2026 Regular Session - Oregon Legislative Information ..., accessed February 12, 2026, https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2026R1/Measures/Overview/SB1522

douglas county oregon, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.douglascountyor.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Minutes/_05202021-157

Pegasus Equestrian | Discover Latest Updates Now, accessed February 12, 2026, https://pegasuseq.com/updates

PE Week Wire -- 11/14-11/24 - Buyouts, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.buyoutsinsider.com/pe-week-wire-1114-1124/

LEGISLATIVE HEARING COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES - GovInfo, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-117hhrg47569/pdf/CHRG-117hhrg47569.pdf

Oregon's top 20 Ag commodities - Natural Resource Report, accessed February 12, 2026, https://naturalresourcereport.com/2024/07/oregons-top-20-ag-commodities/

OREGON AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.oregon.gov/oda/Documents/Publications/Administration/ORAgFactsFigures.pdf

Oregon Releases Updated Top 20 Agricultural Commodities - Morning Ag Clips, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.morningagclips.com/oregon-releases-updated-top-20-agricultural-commodities/

Oregon Grass Seed Commissions Request for 2024-25 Research and Extension Proposals, accessed February 12, 2026, https://agresearchfoundation.oregonstate.edu/sites/agresearchfoundation.oregonstate.edu/files/2024-25_grass_seed_research_rfp.pdf

OSC Releases 2024-2025 Annual Report - Oregon Seed Council, accessed February 12, 2026, https://oregonseedcouncil.org/osc-releases-2024-2025-annual-report/

Oregon's Hazelnut Growers Overcome Barriers - Iowa PBS, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.iowapbs.org/shows/mtom/market-feature/clip/13316/oregons-hazelnut-growers-overcome-barriers

Processors stress need for new markets for Oregon hazelnuts - Capital Press, accessed February 12, 2026, https://capitalpress.com/2026/01/10/processors-stress-need-for-new-markets-for-oregon-hazelnuts/

Prices Up Again! - Hazelnut Growers of Oregon, accessed February 12, 2026, https://hazelnut.com/wp-content/uploads/759426727-gpc_new_profitshareupdate_jul2025_r7_reader.pdf

Death by 1000 Cuts: A 10-Point Plan to Protect Oregon's Farmland, accessed February 12, 2026, https://friends.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Death%20By%201000%20Cuts_2020.pdf

Death by 1000 Cuts: The Erosion of Oregon's Exclusive Farm Use Zone, accessed February 12, 2026, https://friends.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Death%20by%201000%20Cuts%20-%20The%20Erosion%20of%20Oregon%E2%80%99s%20Exclusive%20Farm%20Use%20Zone.pdf

Oregon Wine Industry - Economic Impact Study 2025 - WineAmerica, accessed February 12, 2026, https://wineamerica.org/economic-impact-study-2025/oregon-wine-industry-2025/

2024 Oregon Vineyard and Winery Census Report Published, accessed February 12, 2026, https://industry.oregonwine.org/press-releases/2024-oregon-vineyard-and-winery-census-report-published/

Impact of the Equine Industry on the US and World Economy - The McWilliams Group, accessed February 12, 2026, https://themcwilliamsgroup.net/equine-industry-economics/

Analysis of trends in the growth and development of the equine media in the United States, accessed February 12, 2026, https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/bitstreams/2a0f33c6-6acb-4c36-ae29-8fb3001d9c91/download

Past Legislative Work - Oregon Horse Council, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.oregonhorsecouncil.com/legislative/legislative-work/

State 2024 - League of Oregon Cities, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.orcities.org/application/files/9017/0810/5930/StateoftheCities2024.pdf

Sprawl vs. Smarth Growth: The Power of the Public Purse, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.bostonfed.org/-/media/Documents/cb/PDF/Sprawl.pdf

Understanding the fiscal impact of zoning and how smart growth solutions can foster fiscal responsibility, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.smartgrowthamerica.org/knowledge-hub/news/understanding-the-fiscal-impact-of-zoning-and-how-smart-growth-solutions-can-foster-fiscal-responsibility/

Comments on Metro's Regional Housing Coordination Strategy, accessed February 12, 2026, https://ti.org/pdfs/CascadePolicyonMetroHousingStrategy.pdf

Housing Underproduction™ in the U.S. 2022 - Up For Growth, accessed February 12, 2026, https://upforgrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Up-for-Growth-2022-Housing-Underproduction-in-the-U.S.pdf

A Bipartisan Vision for the Benefits of Middle Housing: The Case of Oregon, accessed February 12, 2026, https://tcf.org/content/report/a-bipartisan-vision-for-the-benefits-of-middle-housing-the-case-of-oregon/

2004 Oregon Ballot Measure 37 and 2007 Oregon Ballot Measure 49 - Wikipedia, accessed February 12, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2004_Oregon_Ballot_Measure_37_and_2007_Oregon_Ballot_Measure_49